News

SEA Faculty, Crew and Alumni Help Unlock Mysteries of Pelagic Sargassum

Sea Education Association alumni, faculty, and crew are the co-authors of a new research paper, Pelagic Sargassum morphotypes support different rafting motile epifauna communities, published June 29th in Marine Biology, that sheds new light on Sargassum ecology. The lead author is SEA alumna Lindsay Martin, C-241, who currently works as a Science Assistant at the National Science Foundation in Alexandria, VA. Co-authors include SEA Professor of Oceanography Dr. Jeff Schell as well as former faculty Dr. Amy Suida, C-142, Dr. Deborah Goodwin, and student scientists Grayson Huston and Maddie Taylor, C-264.

Research for the paper draws on years of data collected by Sea Education Association students from SEA Semester’s Marine Biodiversity and Conservation (MBC) program, as well as additional research conducted by Martin in the Gulf of Mexico as part of her Master’s program at Texas A & M University. In deciding on her research thesis, Martin reached out to her mentor, former SEA professor Dr. Amy Suida, who sailed with Martin on the very first MBC program, and whom Martin credits with providing critical guidance.

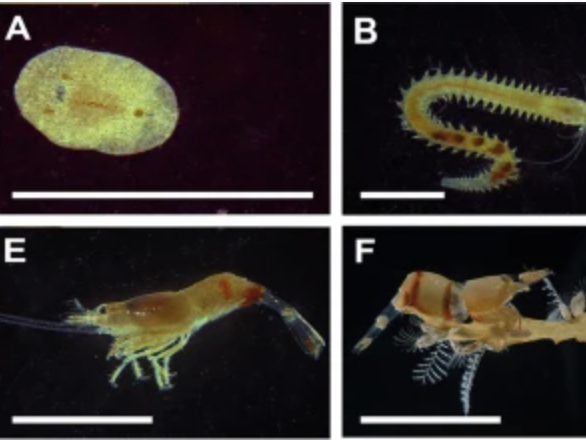

The paper addresses three Sargassum morphotypes (S. fluitans III, S. natans I and S. natans VIII) which are home to different communities of small animals, and examines how small differences between the various forms of Sargassum affects the many organisms that live in the floating seaweed.

Lindsay Martin, C-241.

Lindsay Martin, C-241.

“The pelagic Sargassum ecosystem is utterly unique. It’s the only natural, self-sustaining pelagic ecosystem in the world,” said Martin. But it’s undergoing dramatic change, she explained, noting that there has been a 200-fold increase in Sargassum washing ashore in the Gulf and Caribbean. It’s a major issue, as it destroys beaches and generates bacteria that damage the coastal environment. The problem is the result of huge blooms of Sargassum, the cause of which is not fully understood.

In addition, during the past several years, a previously rare variety of Sargassum, S. natans VIII, has become much more abundant. This newly emerged Sargassum doesn’t support the same wide variety of animals found on other species of Sargassum, which could be important, as the tiny animals found in Sargassum are at the bottom of an important food chain that supports a wider ocean ecosystem.

“Not all Sargassum is the same, that’s the moral of the story,” said Schell. “These results affirm that the Sargassum ecosystem is even more beautifully complex and nuanced than we used to imagine.”

The paper, said Martin, was four years in the making. “Between disparate schedules of people being at sea there were a lot of delays.” Schell described the project as a “wonderfully, collaborative and inclusive effort” that included many SEA students, crew, and faculty. “A heart-felt thanks to the many SEA students who have helped dip net and process Sargassum over the years!” he added.

“These results are an important piece of the puzzle, not only helping us to better understand Sargassum ecology but also supporting a growing amount of evidence that S. natans VIII should be recognized as a unique species. That story however, which is still being written, is for another time,” said Schell.

Martin credits Sea Education Association, and the mentorship of her former SEA professor, for helping to foster her career in ocean research. “SEA was my first ocean research experience ever. It confirmed that working in marine research was what I wanted to do. It turned out to be something I really did love.”

Contact: Douglas Karlson, Director of Communications, 508-444-1918 | dkarlson@sea.edu | www.sea.edu