News

With Newly Published Research, SEA’s Dr. Jeff Schell Seeks to Unlock Mysteries of Vital North Atlantic Ecosystem

By Douglas Karlson

With co-authors and former SEA faculty members Deborah Goodwin and Amy Siuda, SEA Professor of Oceanography and Henry L. and Grace Doherty Chair of Ocean Studies Jeff Schell last month published a paper charting the location and aggregation patterns of Sargassum in the North Atlantic. The paper coincides with research Schell, Goodwin, and Siuda are conducting to better understand Sargassum blooms, and what they may indicate about changing ocean conditions.

The paper, In situ observation of holopelagic Sargassum distribution and aggregation state across the entire North Atlantic from 2011 to 2020, was published last month is the online journal, PeerJ .

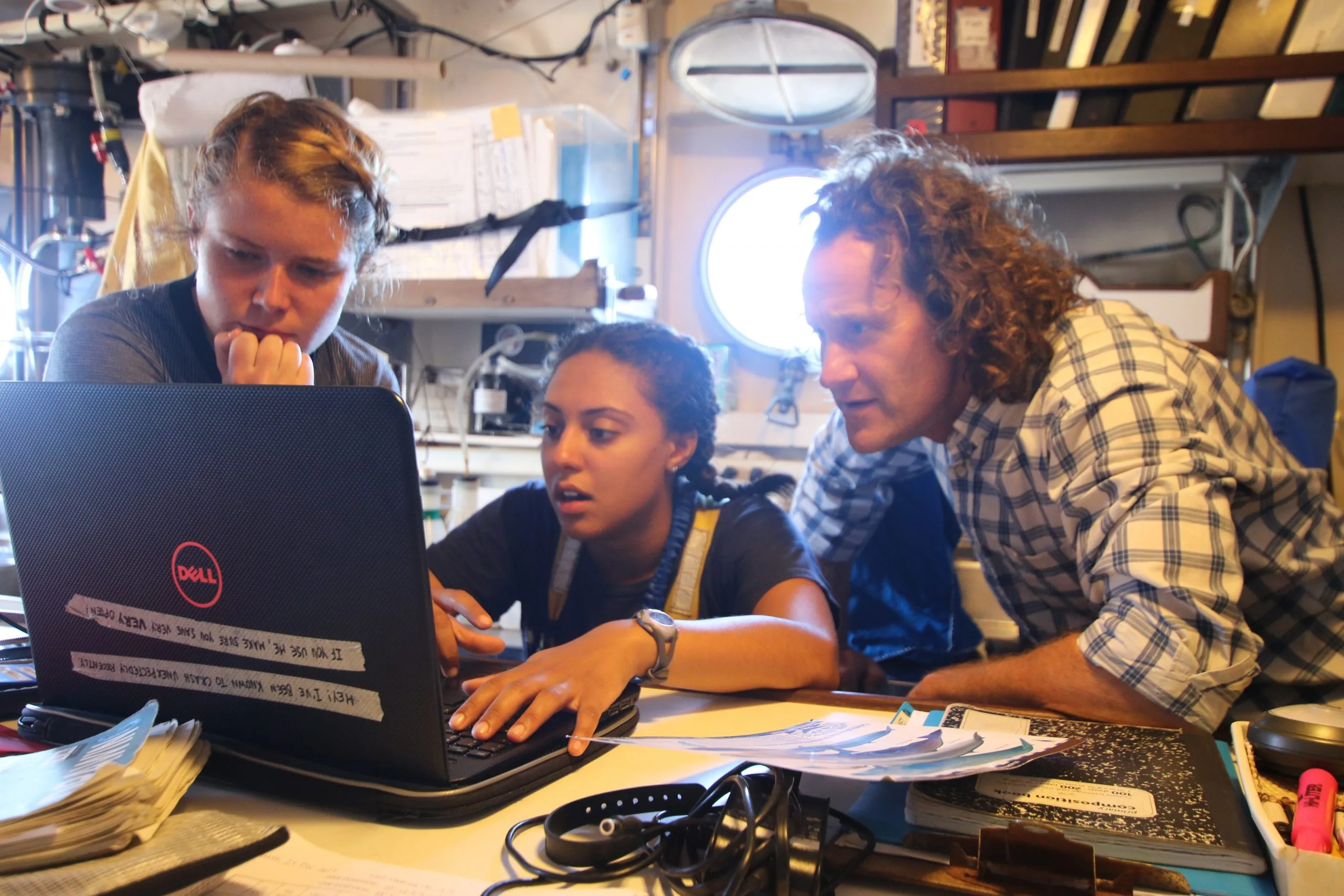

The paper is a detailed geographical analysis of the distribution of holopelagic (or free-floating) Sargassum. The data are based on observations made by students and scientists at SEA over the past decade during which they recorded nearly 7,000 observations over 61 research cruises. Students also documented the various ways drifting Sargassum aggregates or disperses under different wind and sea conditions (see figure 1 from manuscript), which likely influences the ecological value of this drifting, algal habitat.

That process began when satellite imagery first recorded the presence of Sargassum in 2010. Schell and colleagues realized that the satellite imagery missed much of what they had been observing up close. So scientists and students aboard the SSV Corwith Cramer began conducting hourly observations, measuring the size and location of floating mats of Sargassum.

Three predominant types of holopelagic Sargassum have been identified, and Schell explains that researchers at SEA were the first to observe that Sargassum blooms vary in character according to their type.

“Sargassum is an important ecosystem and an oasis of biodiversity on the open ocean, it attracts birds, fish and turtles,” explains Schell. “It’s therefore important to more accurately understand where it’s located and how it aggregates. We need to know where it is because it’s ecologically important.”

As a result of their research, Schell and his colleagues have determined that Sargassum is more broadly distributed than the satellite imagery shows,

In recent years, those massive blooms have begun appearing in the Caribbean, where they haven’t been observed before, and inundating beaches. The blooms span from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico. Schell is seeking to understand the patterns and regional differences of blooms.

“The big question we’re trying to answer is why are big blooms occurring in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean. We think the answers lie in environmental factors. We’re trying understand how temperature, salinity and nutrients affect the growth of different types of Sargassum,” says Schell.

With funding from the Doherty Chair and support of Eckerd College, Schell spent much of the fall in the lab at Eckerd College with fellow researchers Goodwin and Suida. They are doing research to determine if different types of Sargassum have different environmental tolerances and grow better under various conditions, leading to blooms.

In charting the locations of Sargassum, Schell said he and his fellow researchers were surprised to find that the Sargasso Sea is not the source of blooms. Rather, blooms originate independently in the Tropical Atlantic and are transported to the Caribbean following prevailing currents and winds. That, says Schell, could be indicative of larger changes in the North Atlantic.

Noting that blooms used to never occur in the Caribbean, Schell is interested to know if changing ocean conditions are causing the blooms. “Is this the new normal? Has the North Atlantic ecosystem crossed an ecological tipping point?” he asks.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Contact: Douglas Karlson, Director of Communications | 508-444-1918 | dkarlson@sea.edu | www.sea.edu