News

SEAWriter: Coral Reef Conservation: Caribbean (Issue 2, 2024)

Introduction by Katie Hallee

Sea Education Association (SEA) approaches a dawn of new beginnings. Light is beaming from the horizon. Warm shades of orange, yellow, and pink intermingle with vibrant beauty. A vision of radiating magnificence. Do you see it? The sun is rising, and with it, a new era of marine education.

Since 1971, SEA has educated over 10,000 high school, undergraduate, and gap-year students by sailing across the ocean. For the first time, rather than sailing aboard the Westward, Corwith Cramer, or the Robert C. Seamans, students now have the opportunity to embark on entirely shore-based programs. We, the SEA Class L318, are the very first group of students to commence on this new journey in the Coral Reef Conservation: Caribbean (CRCC) Program. SEA has even emphasized this new transition by launching its new logo in the wake of this program and shore-based programs to follow. In this way, we are pioneers. We are laying the foundation. We carry the weight of so many future generations of SEA students.

As a mere seven students, we soon became a very close-knit group. Beginning in Wood’s Hole Massachusetts at SEA’s campus we lived and learned together, quite literally. For the first six weeks of the CRCC program, we stayed in the quaint cottage on campus named Capella. Cooking, cleaning, and studying together, we quickly created a sense of community, bonded by shared interests in the environment, long nights of homework, stargazing, frisbee, and, of course, laughter.

While in Wood’s Hole, we started the rigorous coursework in our four classes: The Ocean and Global Change, Marine Environmental History, Environmental Communication, and Practical/Directed Oceanographic Research. In these courses, we were preparing ourselves for our field component across the four Caribbean islands of St. Croix, Anguilla, Dominica, and Barbados. To do so, we learned local and global factors impacting coral reefs, the history of the islands we were visiting, how to conduct an individual oceanographic research project, and how to effectively communicate scientific information in a diverse range of media.

However, with these lessons, there was always a deeper understanding that there is a responsibility on our shoulders. Compared to other SEA programs, ours is centralized around field based snorkeling research, but also actively engaging with local communities. In this sense, our class was tasked with helping to begin to build lasting relationships with Caribbean partners and foster continued scientific collaboration for the future.

With this weight on our shoulders, but brimming with excitement, we boarded the plane for the first leg of the program, St. Croix! The six weeks to follow were a whirlwind full of immersive snorkeling, meeting new people, and countless new experiences.

This whirlwind evolved my mindset and understanding of coral conservation. When I told my friends and family about this program, I would often get a very similar response. When people heard the words coral, the Caribbean, and snorkeling, they would tend to tell me, “Ah, so you are going to be at the beach all semester. That sounds like a vacation!” Don’t get me wrong, I am incredibly grateful for this unique, diverse, and hands-on research experience. However, what people do not realize is the field of coral reef conservation is incredibly bleak. From speaking to coral scientists across the Caribbean, I have learned that you have to be a strong-willed and resilient person to devote your life and career to coral conservation.

In the media, corals are often still perceived as vibrant and lively underwater ecosystems: an unrealistic beauty standard. The fact of the matter is corals are in crisis. Not just in the Caribbean, but globally. These remarkable animals who are capable of building complex marine habitats are threatened by intensifying stressors: ocean warming, acidification, sedimentation, pollution, fishing, nutrient runoff, and invasive species. These stressors cause corals to bleach, the process of expelling their symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae and leaving their bare calcium carbonate skeleton. Without these algae, corals have to rely only on filter feeding for their energy instead of photosynthesis, previously performed by the zooxanthellae. As a result, corals are dying at an unprecedented rate. Coral scientists must be unyielding in their determination to conservation. They are forced to constantly deal with the reality that corals are

disappearing before their eyes.

This is exactly the reality of Corina and Ryan, the stewards of the Feather Leaf Inn in St. Croix. In

addition to running their eco-hotel, centralized around sustainable and plant-based living, Corina and Ryan are leading coral conservation efforts in Butler Bay. As a class, we had the opportunity to stay in their inn, engage with their environmentally conscious lifestyle, and experience first-hand the implementation of coral restoration. The Feather Leaf Inn uses a drone to conduct wide-scale aerial mapping of Butler Bay to monitor coral health. With this data, Corina and Ryan are working to aid in the spawning of brain coral, replanting corals that have been dislodged, and using a strategy called fragmentation to repopulate the reef from broken elkhorn coral branches. Corina led us on a snorkel around Butler Bay to show us the outplanting they had done. As Corina showed us around the reef, it was shocking to see the extent of bleached coral. Everywhere I turned, the absence of color was overwhelming. Desolate, bright white corals made my heart sink. But then, Corina would dive down and point to her small pockets of hope: successful outplants! I realized at that moment that it takes tremendous inner strength to be in the field of coral restoration, like Corina and Ryan. They continuously create glimmers of promise by persistently believing in the potential of their work.

As depressing as the condition of coral health currently is, I have learned that these strong-willed scientists show up every day on the job, working diligently to combat such stressors. I think this program has brought me a newfound sense of consciousness concerning the complexity of coral conservation as a whole.

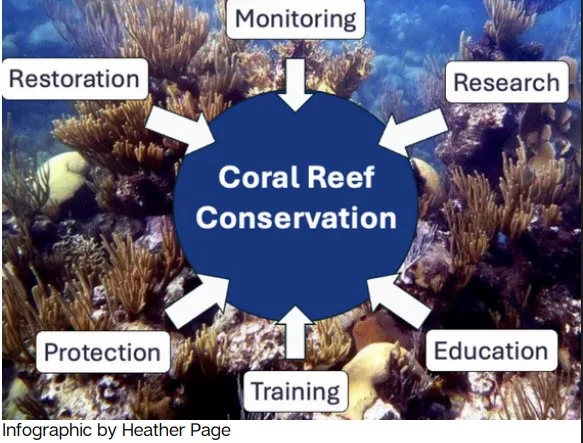

My SEA Oceanography Professor, Dr. Heather Page, has helped me to evolve my mindset to visualize coral conservation as multifaceted. This is because one specific visualization from Heather’s lectures has stuck with me since I first saw it. Coral conservation is the main focus in the center, with six different arrows pointing in. These arrows are labeled with restoration, monitoring, research, protection, training, and education. This attests to the network of factors all influencing coral conservation at once. Therefore, I now have evolved my ideas to believe that we must approach conservation holistically.

For instance, outplanting thousands of coral fragments for restoration will fail to be successful without training more people on how to outplant, researching what areas need those corals the most, monitoring those corals, protecting those corals with legislative action against carbon emissions, and educational outreach to local communities. Each of these factors relies on each other, and to make strides in the field of coral conservation, it is vital to recognize these factors as a whole.

Gaining this newfound consciousness came from seeing and experiencing the reefs with my own eyes. From coral depictions in the media, I also had an unrealistic understanding of what reefs really look like. I saw the massive extent of bleaching and the shift occurring to an algae-dominated ecosystem first-hand. Truly seeing this destruction right in front of me did have the capacity to make me feel hopeless. I constantly would have an internal battle asking, “What can I, as one person, do to save this?”

But then, the fearless scientists I met across the islands, like Corina and Ryan, would pop into my head,

reminding me of their persistence in the face of adversity. This is what made me realize just how special

this study-abroad opportunity was. CRCC prioritized community engagement and cultural interaction. I think that is why I am walking away from this experience extremely hopeful. One can not be a changemaker all alone, it takes collaboration.

In this way, I am honored to have played a part in building connections for SEA across the Caribbean. As a class, we have set up the structure for ongoing scientific partnerships, in turn helping to create greater interconnectedness in the field of coral conservation. In this magazine, as a class, we have compiled a multitude of pieces in a diverse range of media. In our work, you will see our responses to coral reef conservation, the impacts of climate change, and our reflections throughout the program. So, at an epoch in SEA’s history and the rising sun across the horizon, can we take you along with us through our journey?

About SEAWriter

SEAWriter is a student-published magazine, usually created as part of SEA’s Environmental Communications course. Each edition features articles, creative writing, and artwork contributed by program students and faculty. Environmental communication is essential in raising awareness, inspiring action, and bridging the gap between science and society. SEAWriter serves as a culmination of everything students have learned in all their courses and research as well as their field component. Through storytelling and visual expression, students apply their knowledge and creativity to effectively convey environmental messages to a broader audience.