News

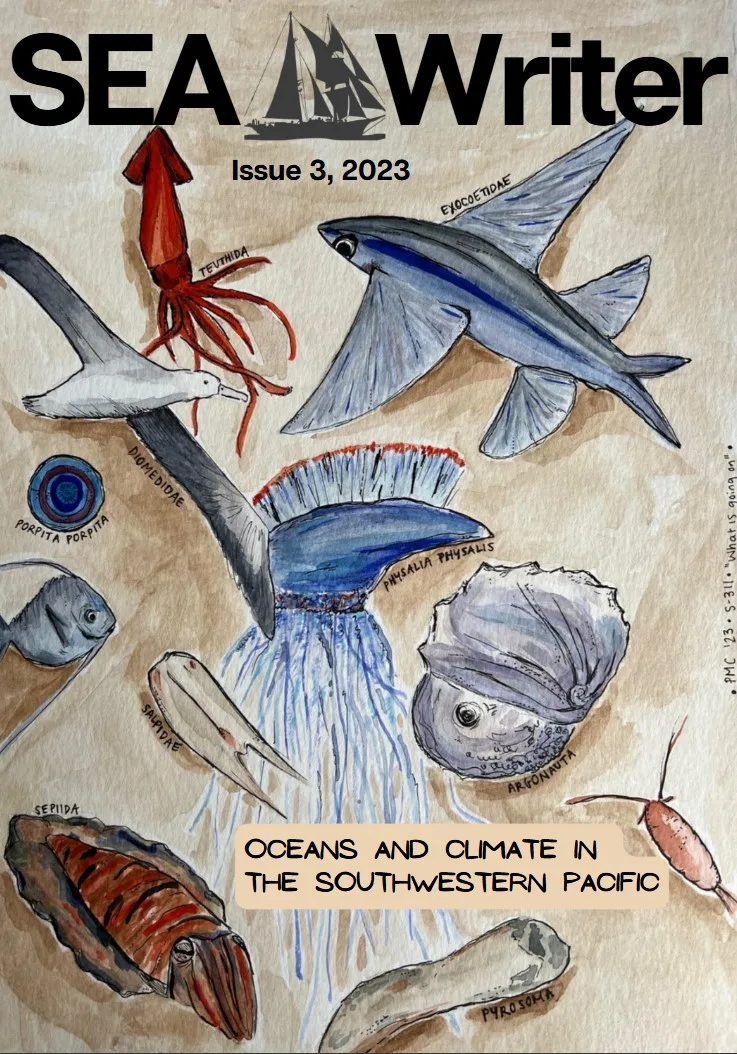

SEAWriter: Oceans & Climate in the Southwestern Pacific (Issue 3, 2023)

Introduction by Grant Carey

We are S-311. A class, a passage, a ship full of people who set out on a voyage. We sailed across the southern Pacific, researching and living in an environment which, even at our most intimate moments, we knew we were merely passing through. The name of our program was “Oceans and Climate” and as we delved into our studies it became incredibly clear how interconnected humanity is with the health of the seas.

After over four wonderful weeks in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, enjoying the end of summer, and preparing for our trip with intensive studies ranging from environmental communication, the oceans and the global carbon cycle, and nautical science, it was time to embark on our journey. We packed up all our gear and journals and flew to Fiji to become crew onboard the Robert C. Seamans, a one hundred and thirty-four foot brigantine rigged tall ship. We spent the next six weeks on board researching and learning about the ocean and life as a sailor. Over the course of our cruise we went to three islands in Fiji, leaving from Port Denarau and stopping in Levuka and Savusavu before setting off to Funafuti, the capital of Tuvalu. The last leg of the journey was from Tuvalu south to Auckland, New Zealand, and it was during these sailing components that we forged a closeness with the sea that few others know.

We began as a group of sixteen individual students heralding from universities all across the US, strangers to a crew of seventeen, and left as a community of 33 shipmates. As we drifted through calm seas, ‘hove to’ as we waited out gale force conditions, and worked the lines to sail we found ourselves constantly learning. Most importantly, though, we were also given the space to reflect: on the state of the environment, our place within society, and our future. It was during one of these moments of reflection on bow watch that I started writing the following letter. I know it is in my voice but I hope that it may yield insight into the life that we lived, the topics we discussed and our hopes and dreams as sailors and students.

To my Elders,

It was the first night of our voyage, and we had just left port Denarau, Fiji, after a few days getting all of our things ready for our journey. The buzz of leaving and watching our stoic ship come to life filled me with joy, and as we motored out of Fiji I was enthralled by the mangroves, the tropical islands passing, and the sunset. My first watch was going to be a dawn watch, starting at one in the morning, and so after finally getting my excitement under the barrels of control, I went to my bunk a little later than I should have to get a good night of sleep. This bunk—a spacious one I am told, but little more than a slot in the wall to crawl into—and the entire ship, was my home for the next six weeks and the wonders ahead of me were countless.

Nature has a funny way of letting you know that in the end it is always in control. This was the first time of the trip that I appreciated what surrendering control implies when living on a sailboat.

I was on the cusp of sleep but my shipmates on watch were setting sails and preparing to leave the sheltered coral sea that surrounds much of the west coast of Fiji and enter into the unprotected ocean. I half left the boat rise into the air as we rode over that first wave and felt my body get compressed into my bunk. Yet as soon as we crested, the wave and the ship crashed down, and with the thud, my eyes shot open and all thoughts of sleep vanished as I felt stomach lurch into my throat. I tried everything: reading, clearing my mind, taking a walk, telling myself that the rolling was not bad, but every crash immediately woke my body. After hours of laying there, exhaustion finally took hold, and I felt my eyes close, thankful for the bliss of getting sleep. A few minutes later I was awakened again—not by the waves, but by one of my shipmates, letting me know it was 0300 and in thirty minutes I would be standing watch for the next six hours. On bow watch I learned that it was possible to fall asleep standing up—a new meaning for exhaustion.

A few days later, this rolling ocean and cramped bunk became a cradle; and me, the baby getting rocked to sleep. The clouds and glistening waves, the stars and moon painted pictures in my memory and showed me new realms for living. It was on bow watch and on helm, feeling the weathered and oiled wood below my hands, that a little voice started to whisper into my ear. Not for the first time in my life and surely not for the last. It told me: this is life. This is what I should be doing. Live the barefoot vagabond life as Bernard Moitessier would say. Live a simple life of working hard, of honing a skill, of venturing to the mountain tops, or mastering a craft. Of forgetting all the ever present tasks that a modern society places upon us. Of doing away with the constraints of a capitalist lifestyle and surrounding myself with nature, adventure, and people who love and care about me as I do about them.

Yet each time I feel this, this call of the wild, this call of music and envision myself in this timeline, I feel a sense of guilt accompanying me. I feel like I am running away from the world, from the dire problems that exist and into a nature that without protection will vanish away. Guilt. Because I have understanding to try and help the world in the face of the environmental crisis. Guilt. Because I could make a difference cleaning up your mess.

Greta Thunberg, a voice of my generation, in her speech to the United Nations said that you, my Elders, “have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I’m one of the lucky ones… We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!” I no longer feel that I have a choice to choose to live how I want, that choice was made for me long before I entered this world.

I became filled with anger. Angst. Rebellion. Unlike Greta, how could I not think that you, my dear Elders, are evil. How could I not be furious at you for robbing us of our future, for tearing apart the natural world, for sowing destruction for money. It is nor earth you are killing, it is not life as a whole you are destroying. No. Those will exist long after we are gone. You are stealing this world from me, from my children, and their children. Will they get to wander in old growth forests, see schools of fish swimming as they breathe in the salt from the sea? Will they get to lie in a field of grass, listen to the birds sing, and meditate on life as I am doing right now? Will there be a nature left for them to find solace in or will they be insulated from nature in a dystopian world of technological control.

Evil is not the devil whispering in the ear corrupting souls to do bad as I have been taught. No. Evil is a created institution; the foundations of a society that we have built. Colonialism, the patriarchy, consumerism. It is the easy path, laid out so clearly for us to follow. The peaceful, the good; they have never ruled the world. It has been the violent who conquer. It is they who plunder. They, who I had every right to believe to be you.

It is an unfortunate testament to the world that we live in that, on coming back to shore after being isolated for six weeks, I was not surprised to find another war erupting. This violence that plagues us as a society is reflected in our treatment of the natural world. The violence that “paved paradise to build a parking lot,” as Joni Mitchell sang in 1970. We clear cut forests and tear open the mountains to extract. Humanity is here. This is ours.

How can we be so ignorant as a society? Why is it that we think we have all the answers? We think we can dominate, shape, and change the natural world. Evil tells us that this is for the better. For progress. There are those of you who think we can transcend the natural world. This cannot be further from the truth. Humanity is but a mere blip in ecological time, a speck in the cellular wisdom that has evolved over the millennia. We fail to realize that the solutions to the environmental problems lie in the millions of years of ecological evolution and cellular wisdom that brought us into existence. We are not the saviours or stewards of the natural world. No. This world has existed before and will exist after us. We need to save this natural world from our-selves, for ourselves. We can do this by returning to our roots and embracing and learning from the natural world.

The beauty of nature is that it will help us if we let it. In that paved paradise, in that parking lot amidst the concrete jungle, cracks will start to form. In those cracks wildflowers will bloom, raising a delicate fist against the monstrosity that we perpetuate. Goodness, not evil, is that which whispers in the ear, that worms its way through the thoughts and dreams of humans and shines through the cracks. Goodness that influences many of you.

I no longer see you, my dear Elders, as evil. The more I learn, the more I realize that many of you have been navigating this darkness, illuminating the benefits of the natural world and fighting for the good of humanity. We as a generation of youth are not alone. I am reassured as I learn of all the incredible work that has and is being done to improve our relationship with the natural world and with others. We are breaking down the systems that have plagued our species for millennia. We will continue to do this, so we can once again integrate ourselves back into this beautiful planet that we all call home. This is a story of hope. This century can be a turning point for humanity where we shake off the oppression that has gotten us here and walk barefoot through the forest. Living in harmony with nature is the only way to survive and as we rebuild and nurture nature, we can once again rebuild and nurture our soul. For us and for our children.

As you look through this magazine, you may wonder about the connections between the broad array of topics covered in blogs from our time on the ship and various scientific reportage pieces in a range of genres. At the surface they do not appear to relate to what I have been talking about, or with one another. I beg to differ. Moitessier once said, “I am on a voyage to save my soul and humanity.” Let me tell you, though we may not know it yet, we also have ended one such voyage. We are a group of sailors, a part of this generation coping with all that you have left us. In the following pages you will find our stories. They encompass parts of our world view. The ideas of building an appreciation for and understanding of the natural world, living a life simply, and finding our place within it all. Thankfully we are not alone, we are guided by those before us who brought that light and illuminated the darkness. Now it is our turn.

I have realized that I will be the barefoot vagabond, but I will not do that alone. No, I have a duty to myself, to those I may bring into the world, to the birds flying by, one piece of the natural web that we once again can become a part of. My duty is to play my part as a steward to humanity so that we can exist sustainably for generations to come. So let us reach for the stars, to go out and live among them to innovate and build but let us not fail to realize that it is those very stars from which we were made. Do not be the evil that sits back and waits. Everything around us all originated from one action, one reaction. Be the change, no matter how small, it will make a difference.

If I am not following in your footsteps already, will you join me? Will you join us?

About SEAWriter

SEAWriter is a student-published magazine, usually created as part of SEA’s Environmental Communications course. Each edition features articles, creative writing, and artwork contributed by program students and faculty. Environmental communication is essential in raising awareness, inspiring action, and bridging the gap between science and society. SEAWriter serves as a culmination of everything students have learned in all their courses and research as well as their field component. Through storytelling and visual expression, students apply their knowledge and creativity to effectively convey environmental messages to a broader audience.