Programs Blog

Ancient Art and Nighttime Musings

Date: April 14, 2025

Time: 0931

Location: 44° 08.74’ S x 168° 37.99’ W — the High Seas, just E of the International Date Line

Weather: Wind out of the WNW, Beaufort force 4, 13 ft seas out of the WSW

At 1920 last night, I stood lookout just aft of the bowsprit: the farthest forward solid point on the ship. The sun had set an hour before, and the nearly full moon made it even harder to see the few stars that dared to peak out from the clouded sky, its dark gray barely distinguishable from the gently rolling sea below. At watch turnover thirty minutes earlier, 1st Mate Rocky had mentioned that Satya – one of our marine techs – had successfully gotten a star fix. Star fixes mark our geographic position by using the angles of certain navigationally useful stars. From there, we can use our known speed and direction to get a good idea of our position: dead reckoning.

But star fixes require sextants and clocks and calendars. And dead reckoning requires a speedometer and a compass. Looking out on the water, it struck me how hard it would be to know our position, to not get lost, without our instruments. It felt like without them, this thousands-of-miles-long voyage would be impossible.

And yet, nearly a thousand years ago, the first people to arrive on Aotearoa New Zealand – the Māori – made almost the reverse of our own journey. And they did it without instruments of any kind. Their techniques were but one entry in a long and storied tradition of oceangoing Polynesian navigation.

For centuries, the many island peoples of the Pacific plied the ocean waves in outrigger sailing canoes, navigating thousands of miles of open sea with nothing but their senses and the knowledge in their minds. Polynesian navigation relies on memorizing patterns in the world around us and how those patterns present themselves at our departure point, destination, and in between.

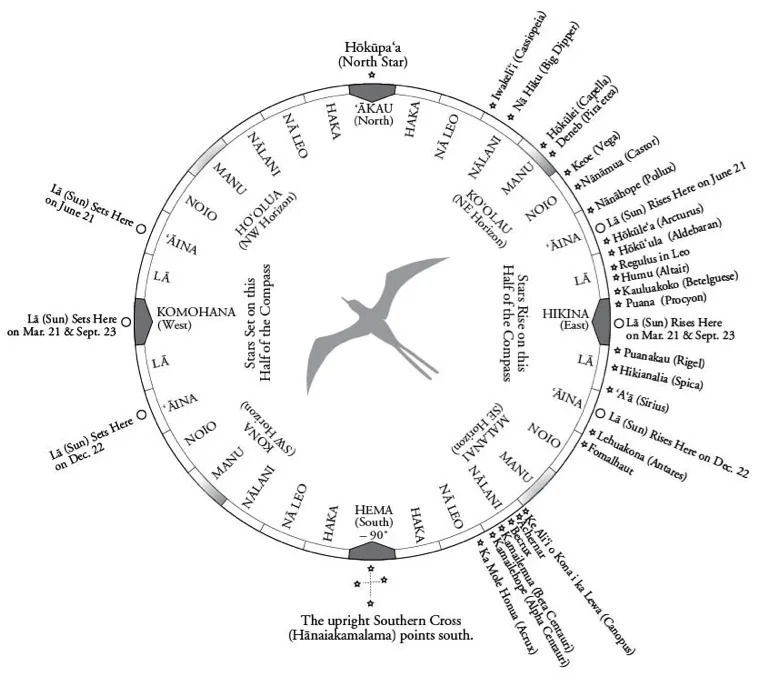

One of the hallmark techniques of Polynesian navigation is the memorization of the rising and setting points of stars on the horizon. By remembering where stars rise and set – their houses – and where islands are in relation to those houses, you can plot a course.

But that only works if you can see the stars, and clear skies are far from a given out here in the middle of the South Pacific. So, Polynesian navigators also make use of other tools. The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but the exact location depends on the season and is only reliable at sunrise and sunset. Distinctive clouds form over islands, and knowing the behavior and ranges of specific bird species can point you towards land.

But last night, with a clouded sky and only the flickering shadows of the occasional albatross, only one Polynesian navigational technique would have been usable. It’s one that I find the most daunting and impressive: the art of reading ocean waves and swells.

Waves are the undulations in the sea’s surface caused by the local wind conditions, which can shift frequently day to day, hour to hour. Swells have deeper origins, rooted in the great underlying patterns that traverse whole oceans. Here in the South Pacific, ocean swells propagate through the water from the west, carried by the westerlies – prevailing winds that blow all the way from Australia to South America. But differentiating swells from waves can be challenging, and on a cloudy, moonless night, must be done by feeling how the boat beneath you rolls and sways and twists.

I am no Polynesian master navigator. I still need my sextant and clock and calendar and compass and speedometer to tell me where I’ve come from, where I’m going, and how to get there. So, as I stood out there scanning the horizon from the bowsprit, I just braced for the next rolling wave.

– Andrew Patterson, Hamilton College, B Watch

Shoutouts:

Mom: Happy belated birthday! Love you!

Dad and Christina: Congrats! Sad I couldn’t be there, but I fully expect Rocky was wearing his suit.

Ash: There’s so many people here I want to tell you about, that I want you to meet, that maybe you would’ve met anyway in the long meandering path through life that I know you would’ve led. I have so many stories that I want to tell you. Maybe I will tell you one day. One day.

Recent Posts from the Ships

- Ocean Classroom 2024-A collaborative high school program with Proctor Academy

- Collaborations and Long-term Commitments: SEA’s Caribbean Reef Program Sets a Course for Coastal Programs that Compliment Shipboard Experiences.

- Sea Education Association students prepare for life underway using state of the art nautical simulation from Wartsila Corporation.

- SEA Writer 2022, Magazines From the Summer SEA Quest Students

- Technology@SEA: Upgrades Allow Insight into Ocean Depths

Programs

- Gap Year

- Ocean Exploration

- High School

- Science at SEA

- SEA Expedition

- SEAScape

- Pre-College

- Proctor Ocean Classroom

- Protecting the Phoenix Islands

- SPICE

- Stanford@SEA

- Undergraduate

- Climate and Society

- Climate Change and Coastal Resilience

- Coral Reef Conservation

- Marine Biodiversity and Conservation

- MBL

- Ocean Exploration: Plastics

- Ocean Policy: Marine Protected Areas

- Oceans and Climate

- Pacific Reef Expedition

- The Global Ocean: Hawai'i

- The Global Ocean: New Zealand