Programs Blog

The Wonder of Sails

Date: April 10, 2025

Time: 1700

Location: 42˚ 15.8’ S x 176˚ 45.5’ W

Weather: Wind from SxW, Force 5, seas 10ft.

We’re sailing!

This is Henry Penfold, writing in after a lovely afternoon watch! Since shutting off our engine at 1900 on April 8, we have been moving under sail power only. We spent the first two days of our voyage motor-sailing north from Lyttelton to avoid a low-pressure system, turning east as we passed Castlepoint to sail along the upper edge of the south-bound system.

For the past several days, our journey has been characterized by rolling seas that have accompanied the weather system we are skirting. Sustained winds between Beaufort force 3 and 8 have built the seas to 10-15’, with occasional 20’ waves. Our anemometer clocked one gust at 63kns on the night of the 8th, just shy of hurricane force. For reference, a knot (kn) represents one nautical mile per hour, with one nautical mile equaling 1.15 statute miles. Since the prevailing winds have been considerably lower than that errant 63kn gust, the wave size has not grown past 10-15’. The Robert C. Seamans is an excellent place to be in these conditions, making even the largest waves look small as they pass beneath us. Our barometer’s needle has been rising steadily for the past two days, a sign of fair weather to come.

Under these wind conditions, we have a fairly minimal sail plan. Of the nine sails we carry (mains’l, main stays’l, fore stays’l, jib, jib tops’l, tops’l, fisherman’s stays’l, raffee, and storm trysail) we have set just three: the main stays’l, fore stays’l, and storm trysail. These sails are all relatively small, and their modest sail area ensures that the gusting wind does not overpower us.

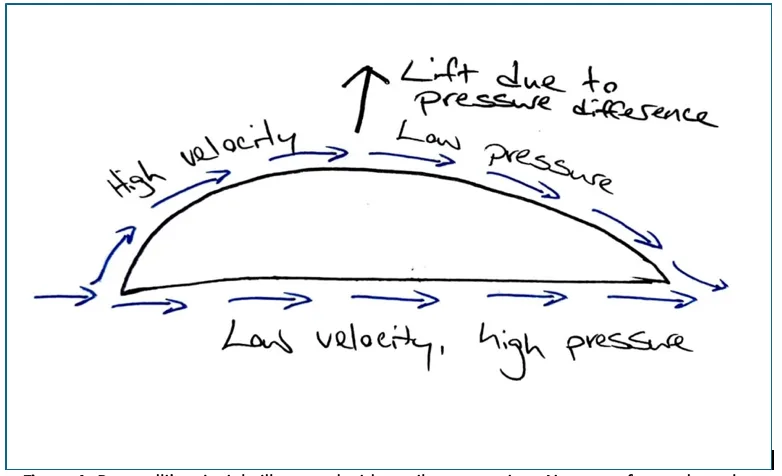

It feels magical to move forward using only the power of the wind. It is worth briefly considering the physics by which our sails harness the wind. Contrary to common belief, the wind does not propel us forward by simply pushing on our sails. Rather, our sails generate forward lift by redirecting air around their edges and creating a pressure differential, with an area of low pressure in front of our sails. This pressure differential is achieved via the foil-like shape of an inflated sail, with a longer and shorter side. In accordance with Bernoulli’s principle, air moving around the longer side of the sail moves faster than air moving around the shorter side. Since air pressure decreases as air velocity increases, a pressure differential is created. The resulting force is lift, which propels us forward into the area of lower pressure (Fig. 1).

Considerations of physics aside, heavy weather has made for an exhilarating departure from Aotearoa New Zealand. Clattering dishes, bouts of sea sickness, and frequent moments of awe at our surroundings have created a lively atmosphere onboard. Against this background of excitement, we have been treated to sightings of rare Hector’s dolphins (an endangered species endemic to New Zealand’s coastal waters) and albatrosses skimming low between waves. Though I look forward to smoother sailing, it has been fun to experience these conditions!

Shoutout: Happy birthday Ian!

Recent Posts from the Ships

- Ocean Classroom 2024-A collaborative high school program with Proctor Academy

- Collaborations and Long-term Commitments: SEA’s Caribbean Reef Program Sets a Course for Coastal Programs that Compliment Shipboard Experiences.

- Sea Education Association students prepare for life underway using state of the art nautical simulation from Wartsila Corporation.

- SEA Writer 2022, Magazines From the Summer SEA Quest Students

- Technology@SEA: Upgrades Allow Insight into Ocean Depths

Programs

- Gap Year

- Ocean Exploration

- High School

- Science at SEA

- SEA Expedition

- SEAScape

- Pre-College

- Proctor Ocean Classroom

- Protecting the Phoenix Islands

- SPICE

- Stanford@SEA

- Undergraduate

- Climate and Society

- Climate Change and Coastal Resilience

- Coral Reef Conservation

- Marine Biodiversity and Conservation

- MBL

- Ocean Exploration: Plastics

- Ocean Policy: Marine Protected Areas

- Oceans and Climate

- Pacific Reef Expedition

- The Global Ocean: Hawai'i

- The Global Ocean: New Zealand