Programs Blog

Back on the Move

Author: Grace Augspurger, Middlebury College

Ship’s Log

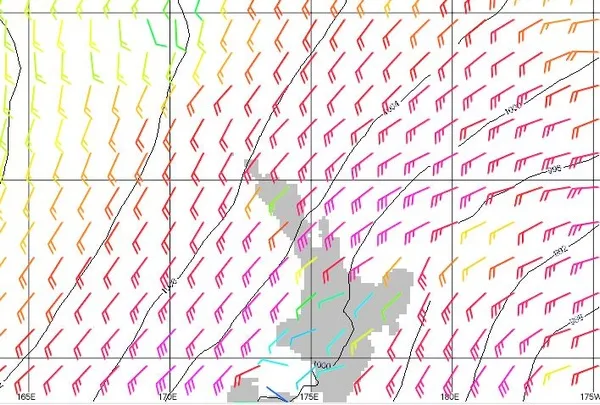

15 December 2023Current Position: 34 41.970’S, 178 23.694’EShip’s Heading and Speed: 165′ true, 5.1 knotsWeather: Overcast, 10-15 knots

Hello again outside world! I’m sure you’ve heard of our trials and trepidations over the past 60 hours, but as of yesterday evening we are finally on the move. The winds and seas calmed down shockingly quickly, and everyone finally got some much-needed sleep. Through the gale (mostly near-gale), many of the normal watch activities stopped. No one at the helm, no lookout on the bow, and no science deployments. One of the few routines that continued as normal was our 6-minute bird observations, which has grown to be one of my favorite parts of lab: at the top of every hour, anywhere from one to four or five watch members stand on the quarterdeck and look for birds. Shouts of bird! ring out anywhere from every ten seconds to only once or twice over the six minutes. Sightings, along with the current conditions and any other marine life and marine debris, are recorded for one of the student projects on seabirds. The most common birds are shearwaters, petrels, and fairy prions, all of which we have learned to identify from great distance based only on the flight patterns, but by far the most magnificent of seabirds is the albatross.There are three species of albatross found in the Southern Pacific: the royal, the wandering, and the mollymawk. Royal and wandering are both species of ⌠great albatross, the largest of all seabirds. Royal albatross, the majority of our sightings, have a wingspan of 10-12 feet, and wandering up to 15! They both have mostly white bodies with wings that are black on top and white on the bottom, with a black band around the back. Royal and wandering albatross can be distinguished by the dark specks on the wandering’s chest, while the royal is all white, and the lack of coloring on the royal’s tail, while the wandering has a band of black. Mollymawks are a smaller species, with a wingspan of 6-8 feet, and are distinguished by their dark backs.Albatross can live up to 50 years and mate for life, although the stress of climate change has been causing albatross couples to get divorced! They feed mainly on squid at the surface, but have also been seen fully submerging looking for food. Noted for their gliding flight, in heavy winds they can sail for hours with no perceptible movement of the wings. Albatross prefer the cold windy climate of the southern hemisphere, and would be extremely elusive if not for their tendency to follow ships for the food source. This behavior may be what led to the legend that albatross carry the souls of dead sailors (and to the saying, to wear an ⌠albatross around one’s neck).I hope you enjoyed learning about albatross; we have certainly enjoyed their company!Grace AugspurgerMiddlebury College

https://sea.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/S312_15DecPhoto2_small.jpg

Recent Posts from the Ships

- Ocean Classroom 2024-A collaborative high school program with Proctor Academy

- Collaborations and Long-term Commitments: SEA’s Caribbean Reef Program Sets a Course for Coastal Programs that Compliment Shipboard Experiences.

- Sea Education Association students prepare for life underway using state of the art nautical simulation from Wartsila Corporation.

- SEA Writer 2022, Magazines From the Summer SEA Quest Students

- Technology@SEA: Upgrades Allow Insight into Ocean Depths

Programs

- Gap Year

- Ocean Exploration

- High School

- Science at SEA

- SEA Expedition

- SEAScape

- Pre-College

- Proctor Ocean Classroom

- Protecting the Phoenix Islands

- SPICE

- Stanford@SEA

- Undergraduate

- Climate and Society

- Climate Change and Coastal Resilience

- Coral Reef Conservation

- Marine Biodiversity and Conservation

- MBL

- Ocean Exploration: Plastics

- Ocean Policy: Marine Protected Areas

- Oceans and Climate

- Pacific Reef Expedition

- The Global Ocean: Hawai'i

- The Global Ocean: New Zealand